A 9 Year Old Boy and a 3 Pound Tin of Calcium Carbide

“Hey Wog, did you ever blow anything up as a Kid?” – Eric in a teen camp

Prelude

My folks lived in the suburbs where I spent much of the school year; I spent my weekends and summers on my aunt’s farm, I would rather dig a trench in that hard red dirt than be at school. All week long I looked forward to Friday so we would head back out to have another short adventure or a vacation but three months on that farm was over before I knew it. Time was different there, Dad said, “When you drive in to Arizona you set your watch back an hour, when you stepped into that old cabin you set your calendar back 40 years, you can smell it.” When you stepped into her tiny cabin it did have a distinctive smell that only very old buildings have. It was smells of the past absorbed into the woodwork; it was a smell creosote from heating with wood, bacon grease in the kitchen, smoke from the kerosene lamps, and percolated coffee. The same activities that would have made up life. Every evening we would be greeted with an orange glow from the fire in the stove and the flames of the lanterns. A black rotary phone and a tub radio were the only artifacts that gave away that we were not in the 1930s. That phone and radio could have been props on a movie set, in all my years out there I never heard the phone used you would not fire up the truck to get something from the feed store unless you needed enough to justify the trip so there was no need to call a head to see if they had something because there was always a list that had been growing from last week’s visit. If my aunt wanted to have a conversation with people she wanted it face to face. The radio I think I was the only one to ever have it on and I think they got it for me, yet is was new when Truman was president. The only time it would be on is if I was alone usually during the week when my aunt and uncle would retire before it was too dark to navigate the house to make it to bed without wasting kerosene. The soundscape was made up of coyotes off in the distance, frogs down in the creek, crickets, the crackling flue of the woodstove, and of human conversation. The conversation was stories of the good Ol’ days of 1890 to 1930 and everything in between. I would sit and listen to the stories as I would whittle on some project or thumb through books that were printed before electricity was in homes and people went to work in cars. My assigned sleeping arrangement was on the wood box under the window near the wood stove which was the focal point of activity each evening. I would listen to the stories trying to fight off sleep not wanting to miss a word. The scene could have been out of To Kill a Mocking Bird if not for the regular B-52s flying over the cabin as they took off from Strategic Air Command stationed at March Air Force Base. It was always the start of an adventure for me.

After 50 years, if I smell a century old cabin or see the flickering light of a fire it takes me back to the stories and adventures of my youth out on the top of that piece of wilderness. During our teen camps sitting around the campfire I tell stories of my past and the story I am about to tell I have been asked to tell for years. I have been told that every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. I will start at the beginning, it will set the stage.

My mother and father were neat, organized, and dad kept everything sharp be it the crease in his slacks or the edge on his plane-irons; his mantra, a place for everything and everything in its place, sharpened, cleaned, and oiled. My aunt and uncle, well, not so much, before I could do a job I had to find it, fix it, and sharpen it. My folks were teens during the depression, my aunt in the 1910s her husband in the 1890s. I think the depression was harder on the adults during the Great Depression than on the kids. My aunt kept everything for fear there would be a time again that you could not get what you needed. They were still using things from the depression and before; in a many ways they were still living in the depression. I learned as a kid most any job started off with needing to dig a hole or a trench that first weekend of summer vacation was no exception.

“Uncle Becher? Who’s WPA?”

“Who?”

I held up the pick and pointed to the initials stamped into the socket and I read, “WPA.”

“Well Boy, it’s your great uncle Walter Peter Alders,” and he spit out his roll-your-own into the ditch and looked away and rolled another not saying anything. In time he looked at me and said, “He gave a lot of people work when there wasn’t any.”

“Well… I never heard of him before.”

“Well… He’s what you call the black sheep of the family.”

“I thought you were the black sheep of the family.”

He glared at me with one eye, “Who told you that?”

“You did.”

He smiled showing his coffee stained teeth. I don’t think he believed me but I wasn’t going to say your wife. Without saying much we continued to work on the trench him swinging the pick into the hard as brick clay and me spooning what little dirt he could break apart out. When we heard my aunt yell, “Foods ready,” he filled the long depression with water and we headed in.

After we ate Dad relieved his bother-in-law and we continued to dig down to the offending pipe the water made the going a bit better.

“Tell me about Wade Peter Alders?”

“Who?”

“Uncle Wade Peter Alder.”

“Don’t know who you are asking about. Who’s Uncle?”

“Becher told me he was my great uncle. His initials are on this pick and that shovel.” I pointed to the WPA stamped on the pick dad had in his hands.

Dad chuckled but did not smile, “Work Progress Administration, it was a Government program during the depression to give work to those that couldn’t find any. Becher worked for them, they built roads, bridges, and schools. The auditorium at your school was made by the WPA.” We continued to dig “Best not to bring up the WPA to him again, it was a hard time.”

In time I learned that at the end of WPA projects the tools were scrapped and Beacher would bring them home, when the train put in electric signals the kerosene lamps were scrapped, when the miners started using battery powered flash lights their carbide lamps were scrapped, when you could get acetylene in welding bottles acetylene generators were scrapped, these relics where the stuff of daily life on my aunt and uncle’s old farm.

The Tin

My uncle slamming the wooden framed screen door bringing in an armload of kindling finished waking me up. My uncle had started his day before the stars started to fade, he said his first job of the morning was to wake the rooster to get it to crow. It was my first job of the day to get a fire going in the woodstove to take the chill off the house, get the coffee percolating, and the stove hot enough to fry the bacon, eggs, and corn meal mush. It was the last year my age could be counted in single digits, it was 1967, in a few hours somewhere the Monkey’s would be playing on a color TV, but not on this little desert farm, which was stuck in the 1930s. We could get 3 radio stations on the Art Deco tubed radio, Marty Robins was singing about a west Texas Town on one, Bobbie Gentry was singing about throwing something off a bridge, and news about the Vietnam War wwas on the third station that was our only contact with the outside world, but no one much cared for what was going on outside of our own little world. After getting the fire going I would crawl back into my Sears and Roebucks cotton sleeping bag and nod off as I watched my uncle make the first meal of the day with his unlit roll-your-own hanging from his lip. The coffee and bacon aroma would fill the cabin as he would fry them on that old cast iron skillet. The same pot of coffee had been percolating on that wood stove since Roosevelt was in office. The pot was white enamel but stained a black-brown from a century of use, and the coffee that came from that pot would float a horseshoe. I think, like my aunt’s sourdough starter, her “coffee starter” came out on route 66 in ’37. The screen door slamming was my cue to get up. Like the big man that I thought I was, I poured myself a cup of that coffee but nearly gagged trying to get that bitter black liquid down. It was said by my other aunts and uncles that Ozark moonshine was smoother than that coffee. I am not sure about that but they said it, well I guess it must be so. I think Eisenhower was in office the last time that cup had been rinsed out and that moonshine would have been put to good use as solvent to clean the coffee tar from that tin cup. As I waited for the cup to cool I scraped the tar of the coffee off the handle with my thumb nail. By this time there was but a few coals left my uncle had left me an egg, fried cornmeal mush, and 3 strips of bacon all floating half submerged in warm bacon grease in the skillet. The egg was crunchy and the bacon floppy and a tortilla to fold it all in.

The last of the stars had disappeared as I let the old wooden framed screen door slam with my old single shot 20 gauge in hand and my three shot shells in my rear jeans pocket. It was my job to sit and thin out the cottontails, jack rabbits and ground squirrels from the garden. If I got a rabbit or the sun was about two fists above the horizon my morning hunt would be over. I would leave the garden and let the flock of 100 Rhode Island Red hens out of the chicken coop, fed and watered them and fed and watered my own rabbits. Then I would go down to the creek and play. When the sun was just above the trees I would head back up to the garden hunting ground squirrels along the way. If I heard the bombers or fighter planes I would climb up on to the roof of the white shed and wave at the pilots as they would complete the turn to fly over our small farm out in the desert. Sometimes the fighter pilots would do some trick to tell me they saw me wave. Then to the house for my second breakfast and find out what chores or adventures were enstore for the rest of the day. That was my Saturday morning routine.

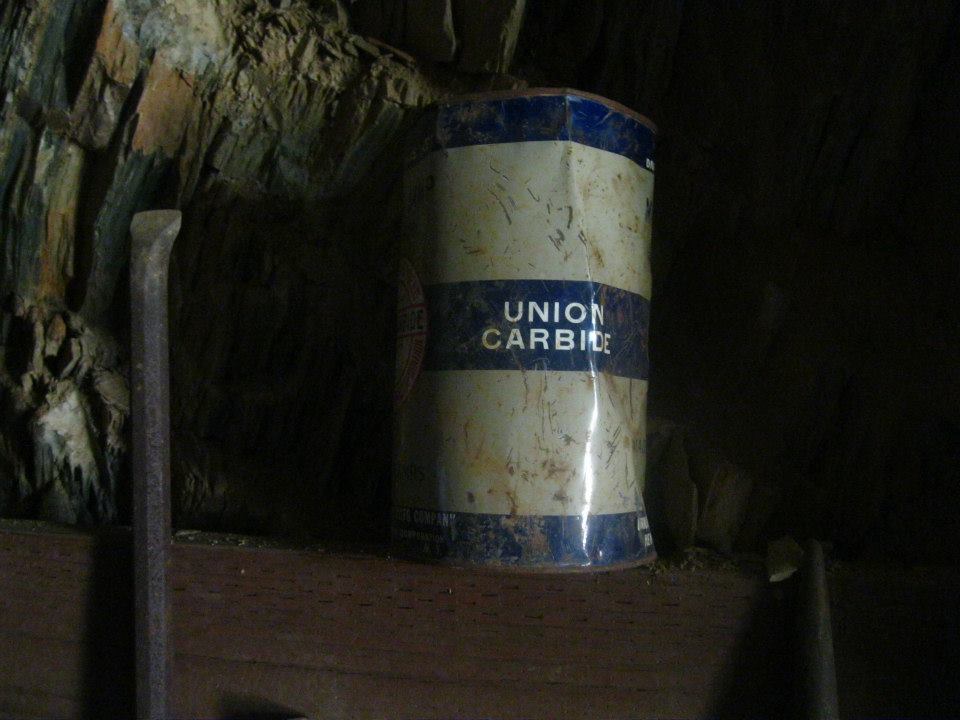

As I passed the barn on this particular day Becher was coming out of the barn holding a tin and yelled: “Boy” my uncle looked like he was from a Steinbeck novel; Becher in his felt fedora, blue denim over-alls, red plaid flannel shirt, lace up work boots, and a roll-your-own always hanging from his upper lip. He yelled again, “Hey, Boy, I got something for you. I don’t think we will ever have a call to use this again.” In his scarred wrinkled carbon stained hand was a dusty tin, painted white and blue and speckled with rust. The only words on the can was Calcium Carbide, Union Carbide, 3 pounds, 1/2 inch lump, nothing else. As he handed me the tin he said, “Go have fun Boy.” I said “Gee Thanks.” I had no idea what he just handed me or how I was going to have fun with what sounded like a can of rocks, “Ah… What I do I do with it?” “Ask your dad.” He smiled only with his eyes which told me this was going to be fun. He was my age in the 1880s in the hog belt of Illinois and they knew how to have fun back then. As I was walking back to find dad my shot gun in one arm and 3 pounds of calcium carbide in the other.

Nearly out of ear shot Becher yells, “But be discrete.”

Well we didn’t have a smart phone back then, you were lucky to have a transistor radio, and what I had instead of google was a 1936 Funk & Wagnall New Standard Unabridged Dictionary. I could get as side tracked with it just as I could with the internet today. So what I learned from my dictionary that morning was, “Be discreet,” meant, best not ask dad. What I learned next was that calcium carbide was used in miners lanterns, car head lamps, and welding. That when added to water it produces acetylene gas. Next I learned acetylene or C2H2 is a colorless gas used in illumination, welding, and cutting metal, it is highly flammable and explosive gas, Me “Oh Boy this is going to be fun.” It wasn’t 10 AM and I had added three new words to my lexicon and yes I had more confirmation that Beacher knew how to have fun.

The next morning my folks were heading back home to Placentia and I am spending the week on the farm out in Woodcrest. I spent the night engineering in my head what I was going to do with my source of explosive gas. It involved an empty grease can, gas lawn mower, an old spark plug, a 100 foot 12 gauge extension cord, a soldering iron, and of course a 3 pound tin of 1/2 inch lump calcium Carbide. As soon as I could see the dust from Dad’s car disappear in the distance I started assembling my blasting setup.

My goal was to have fun but not have any part of me meet my maker and it is much more fun if you have to do a bit of engineering.

Building Cape Canaveral West

When I was in kindergarten for Christmas I was given an erector set, the parts to build a crystal radio, and my first soldering iron (to this day the smell of melting rosin core solder takes me back to my boyhood). By age 9 I had a collection of old soldering irons and soldering coppers and mastery of soldering various metals of various thicknesses; at age nine my preferred method of building. I plugged in a soldering iron that the coil was as big as my wrist (not sure if that is a testament to how big the iron was or how skinny my arms were) pulled the sparkplug from the lawnmower, gave the old sparkplug and the lid of the grease can a lick with the wire wheel and brushed it with acid, I cut an x in the center of the can with a chisel, stuck an old pipe in an inside diameter just bigger than I thought was going to be the outside diameter of both the sparkplug and the sheet metal of the lid. Mounted the fitting in the vice with the hole up, put the x in the center of the pipe fitting, with a sparkplug held in a socket and a farm made lead mallet with all the wallop my skinny arms could do drove the old spark plug into the x of the lid made a perfect mating of the sparkplug and the lid. When struggling to get the sparkplug lid assembly unscrewed from the pipe fitting I was beginning to think the pipe union was going to be part of my assembly but I was bound to stick to the original engineering. With the aide of an old truck inner-tube for grip and much grunting and grimacing I got it unscrewed from the fitting.

A lick of a smooth file on the soldering copper before the flowing blue color faded, a quick brushing of acid and quick tinning of fresh solder the iron was ready, a fresh brushing of acid on both the lid and sparkplug now it was ready for solder. The one inch copper soldering iron proved to have sufficient heat to permanently solder the lid to the sparkplug so the sparkplug would not become a projectile and to provide a perfect gas seal. I removed both ends of the extension cord and soldered all three conductors to the sparkplug wire on the lawn mower and the other end to the post of the sparkplug. I was thinking to myself this assembly was going to make an antenna, if I hooked up to a running truck engine it would probably jam all the radios all the way to March Air Force Base, probably not an idea to entertain.

I lugged everything I needed out to the last hose bib on the property out past the garden, out past the storage shed and out past the chicken coup about 400 feet from the house and more than a mile from the closest neighbor. I ground the mower to the water pipe and 100 feet away I raked 16 foot diameter circle clear of weeds for my test pad so I would not set the place on fire. My rules growing up were don’t poke your eye out or burn the farm down and always come home with the same number of fingers I left home with that gave me a lot of freedom to explore and learn, the reality was my own personal boundaries seemed to get tighter rather than being imposed on me by adults. Those self-imposed limits always seemed to be preceded with me saying, “Dang!!! I best not do that again.” But I fear I am getting ahead of myself. In the center of the circle was the grease can with about a quart of water, I dropped a lump of calcium carbide into the water and the white opaque explosive gas immediately started bubbling from the gray lump and got my first sniff of the distinctive smell of acetylene gas. I quickly hammered the lid back on the can and ran back to the mower. Not sure when I had waited long enough I can see the lid start to bulge, I pulled on the mower rope the magneto made electricity to make a spark and bam the lid blew off the can. It made a low pitch report about as loud a noise as a 12 gauge shot gun but not my 20 gauge. Before I knew it the sun was droping below the horizon and I could now see the red flash of flame coming from the can. I stashed the tools of my new trade in the closest shed and head in to have my now cold supper.

When I came in the cabin my Aunt said “Boy, you must have gone through 100 shells today. Where is the Winchester?” Not thinking I pointed to it in the corner where it leaned most of the day. “Right there.”

Becher was looking down trying not to laugh.

Dolly asked, “How did it get there?”

“Magic I guess?” Me now trying not to laugh and Becher trying not to choke on his coffee.

“What have you been doing all day?”

“Just practicing Aunt Dolly.”

Before she could get out her next question Becher said, “Boy give me a hand outside.”

As we walked to the cordwood pile I said, “Thanks Uncle Becher?”

“We best head into town and get some shotgun shells and some clay pigeons.”

The Cover

We started the next day with a trip to town to the feedstore to get some lay mash, shotshells, a case of clay targets, and two ice cold orange sodas. As money was being passed back and forth at the register I spotted a dusty can of Union Carbide, calcium carbide on the shelf. I pointed at it and winked and asked, “Can you still get carbide?”

“Oh, yes there is still some old guys that still use the stuff. You need some?”

Beacher said, “No still have a can, but good to know I can still find it.”

When we got back he sent me in the house to get our 2 shotguns and meet him at the chicken coop as he went into the shop. At the chicken coop he met me with his 41 ford flat bed with some 2 by 4, a length of angle iron, bailing wire and an empty paint bucket. We wired up a teepee put a nail in a hole he drilled to the right of center of the angle iron nailed a couple blocks to limit the swing, and hung the gallon paint can from the short end. He reached down and picked up a handful of dirt and let it fall and watched the direction of the wind. That told me to get ready to shoot. He put enough water in the can to raise the long end and put clay pigeon on the channel next to the fulcrum, got ready with the shotgun and he poked a hole in the can and the water started to drain out. On cue the long end dropped and circular the clay disk picked up speed rolling down the angle iron and fell to the ground but I shot at it missed and it broke to pieces. Beacher grabbed some of the weed I piled up the day before to catch the clay targets so they would not break if I missed them. In a short time I was starting to hit most and we figured out the proper amount of water so I had the time to load the clay disk walk back to the shooting line and pickup my shotgun and load the shotgun and be ready to shoot. It was brilliant took about the same amount of time to setup between shots as it took to load and fire my carbide contraption, it sounded nearly the same, and was about as much fun and was a challenge. After we both shot at clay pigeons a number of times he had me demo my carbide set up, his smile and chuckles were accolades enough. How he could laugh and not have his roll-your-own drop from his lip was a mystery. Had me set it up again put an empty can of peas on the lid next to the sparkplug and fill the can with broken pieces of clay pigeons. I pulled on the rope the explosion launched the can and he shot it out of the air never losing his roll-your-own. “Beacher please don’t shoot the lid.”

“Would that put an end to the fun.” We took turns shooting at his contraption and then at mine.

The next day I was alone again at my engineering project. I learned that I could see the gas because it bent the light as it went through the air, the gas could explode on its own if I waited too long, and no matter how much carbide or water I used at a point I could not get a bigger explosion. Yes, I was on a mission to get a bigger explosion.

It Needs More Oxygen

In an old automotive mechanics book entitled Modern Auto Mechanics, written in 1927, stated the air to fuel ratio should be 14.7 to 1. But that was for air to gasoline and by mass. How was I going to weigh air?

An old applied physics book told me “1 cubic foot of air at standard temperature and pressure assuming average composition weighs approximately 0.0807 lbs. acetylene 0.0727. or 10 gallons of air 0.1296; acetylene 0.1168”

In a Victor torch welding manual stated 3 psi to 3 psi. Cool now we are in volume but air was only 14% oxygen. I only had the math of a 4th grader. Five function calculators were not going to be available for another 8 years. Long division sucked, I hated it, and I sucked at it. It was going to be 4 more years before my father was going to show me how to use his slide rule and I remember how angrily I felt having to have spent all those years doing long division when it only took a second with his Pickett slide rule. But that is another story.

In the shop next to the lathe was an old WWII 30 gallon galvanized corrugated trash can with band iron riveted on both the top and bottom, it weighed empty about what I weighed back then full. That would be about the right volume and weight, for what I was not quite sure. I dumped the steel it held into a couple old wooden nail kegs. In the shop was a 5 gallon galvanized bucket (67 was the first year that the 5 gallon plastic bucket came out it would be a few years before they were a staple on the farm). I drug the trash can down to my ordinance area. Along with a 30 gal plastic trash bag, a bicycle inner tube, 5 gallon bucket, and a pick. My first step was to figure out how much time it took to make 15 gallons of acetylene. I put about 6 inches of water in the bottom of the bucket, the lid with the sparkplug soldered to it, hung extension cord so it was near the top of the bucket. Put a hand full of calcium carbide in the bottom of the trash bag and gave it a few twists, I carefully nearly sealed the bag over the top of the bucket using the bicycle tube and a stick as a tourniquet put the trash bag into the bucket without spilling the calcium carbide into the water pushed out the air then fully sealed the bag to the bucket. I then let the calcium carbide fall into the water as I counted out seconds to fill the trash bag with gas. It took roughly 140 seconds. I pulled the rope just to see what would happen thinking probably nothing having very little air. It let out a funny big belch and a sooty orange flame looking like it mostly burned when it hit the outside air. The soot hung in the air and slowly settled to the ground. Unimpressive, but funny. There was still gas bubbling from the bucket so I put the trash can upside down and over the top. After about a minute I pulled the rope and again an unimpressive boom lifting the can no more than a foot off the ground more just knocking the can over. Experiment #1: too much fuel, Experiment #2: too much air. Experiment #3: well I still needed to do some preparation. With the pick I dug a small trench into the adobe clay soil for the trash can to nest in, I wanted air and acetylene to compress a little like the compression stroke in an engine. It was slow going, a full swing of the pick into that clay soil did little more than make a dent, but I was motivated, my “why” was the biggest boom I could get. About lunch time I had a circle about an inch deep and about 3 inches wide. I filled it full of water and went up for lunch. There was a western fence lizard on a cinder block doing pushups so I did some pushups back at him we did that for a bit then I caught him.

As I let the screen door slam Aunt Dolly said, “Mighty quiet down there, what nefarious thing have you been up to?”

“Catching lizards.” I show her my lizard and carefully lifted the lid on my aquarium turned lizard habitat to join the other 2 now pets.

Tee Minus 10 Seconds

After lunch, reading my book, and a nap I headed down to finish my trench now with an old Gandy bar. With the help of the water and the Gandy bar I was able to dig the trench down a good 6 inches.

The time had come. I rinsed out the bucket, put a heaping hand full of Union Carbide, 1/2 inch lump calcium carbide into a Folgers coffee can, gave the spark plug a couple of licks with the file and re-gapped it (I wanted a really really good spark), and staged the carbide, can of water, and lid on the ground next to the bucket. Pressed the extension cord into a notch I made in the trench to accommodate the cord, everything had to be just right. Even though I still had half a can of calcium carbide, the feed store had a can on the shelf, and the summer was still young, but for some reason I believed this was only going to be a one time experiment.

I added water to the trench to top it off. Just as I went to pour in the calcium carbide into the bucket I could hear a B-52 taking off and decided to wait just a bit to let it get louder to help cover up the report from Experiment #3. When the time was right I reached down and picked up a hand full of dirt and let is fall, seeing that the wind was not going to push the can over the roof the house or the chicken coop I knew I was good for my launch. In fact there was no wind the tiniest dust settle straight down. It was only academic I did not believe that the can could truly get higher than the chicken coop and shed that hid my activities from the main part of the farm.

Just when everything felt right I shouted, “Coming to you from Cape Canaveral it is T minus 120 seconds.” the 100 hens cluck with nervous anticipation. I believe they were hoping this was going to be the last experiment. I poured the contents in from the Folgers Coffee can in the bucket of water, and started to count back from 120, I covered the bucket with the corrugated galvanized banded and riveted WWII military surplus 30 gallon trash can and nested it in the trench. At T minus 10 seconds I could see bubbles starting to come up in the trench. I ran back to the lawn mower and at 0 I yelled “Blast off over the roar of the B-52 and pulled on the rope start on the mower engine.

“Holly Crites Mother of Pearl!!!” I could feel the sound in my chest, my ears were ringing it sounded like a sonic boom . The trash can was getting smaller as it was going up. The roar of the B-52 was nearly defining and the bomber and trash can were now both in my field of view. Time seemed to have slowed down and I could nearly make out B.F. Goodyear on tires of the still down landing gear. As the trash can was approaching its zenith it appeared to me that when it did the Boeing Aircraft was going to share the same airspace at the same time.

I don’t know if the pilots saw the trash can as it was approaching them, if they did I wondered if they thought I did with malice and forethought. Up till now in my mind I had a pretty good relationship with the pilots of both the fighters and bombers. In 2017 the planes are grounded when a three pound drone is in the air I imagine my 30 pound trash can was under the radar and out of their vision until the last second. I can imagine the chatter in the cockpit.

“What is that clicking over the radio? Christ, What in the hell is that?”

“Did you see that?”

“I don’t know what did you see?”

What I saw at a distance no longer looked like a standard WWII 30 gallon trashcan but a gray metal wine barrel that was much more bulbous on one side and with a conical shaped bottom. I truly was scared that the bomber and can were going to hit each other. Time stood still but they eventually passed over the can. Now the can was at its zenith and it just hung there like Wile E. Coyote running off a cliff and not knowing that he should start to fall. I then realized that what was left of the trash can was just getting bigger, not going north, south, east, or west but it was in a slow tailspin, coming straight down on me, no matter what direction I ran it seemed to be chasing me. As I ran, I tripped, fell to the ground, and like we practiced every Friday in our duck-n-cover drills I covered my head and in a breath the can, in its new configuration, struck just a few yards from me and took much more of a bite out of the clay earth than did with that WPA pick and hours of my time.

Terrified I was gasping for air I slowly caught my breath about the time the dust cleared and stood-up to inspect all the damage. The can was now only corrugated near the two iron bands the rivets holes were now keyholes, opposite the riveted and soldered seam was now bulbous, the zinc did not stretch like the 14 gauge tin under it and had a pattern similar to the creeks and rivers of a watershed converging near the two riveted bands. Where it had struck the ground the tin now had five deep wrinkles. The ground where the blast was had dots of orange where the still glowing embers were fueled from roots of the weeds, any loose dirt had been blown away, I was covered with the red clay dust, and all the chickens were hiding under cover and to this day my ears are still ringing.

I was sure Air Force personnel would be showing up at the house in about as much time as it took them to drive out there. So I quickly went to work putting things in a pristine condition, I used a WPA sledge hammer to beat the bottom in so the can could at least stand on end as best as I could. I pointed the blown out riveted seam next to the lathe to hide the most damage and put the steel back in it.

I unsoldered the extension cord from the lawn mover, saw that my uncle had left me a new sparkplug by where the mower usually sat. I cut the cord off the sparkplug, tinned the ends and reassembled the extension cord hung it back on the hook, filled in the ditch, scrubbed out the bucket and put the blue and white tin of Union Carbide, Calcium Carbide, 3 pounds, 1/2 inch lump back on the shelf.

# The End

That night at dinner I was quiet, my aunt asked if I had seen the plane make the sonic boom that she heard earlier. Over the few days officers from the base never came for a visit, there was never a letter from the base. The rest of the summer was much quieter but not adventure free. Near the end of the summer I walked into the shop my eyes had not adjusted from the noon day sun not knowing my folks were there, with his back to me, I heard dad’s voice before I could see him. Dad was leaning against the lathe chatting with my uncle, dad’s eyes caught the trash can tilted his head to the side to get a better look at the bulbous no longer corrugated trash can. “What in the world happened to that?” Uncle Becher, looked past dad, looked me in the eye, smiled and said, “Not sure but I got a pretty good idea.” I had set tighter boundaries for my own personal freedom.

No mention was made about that week for some 40 years. Everyone but me has passed and maybe the flight crew of the B-52 have passed, until around a campfire one night, during a teen camp, one of the teen boys asked, “I bet you blew something up as a kid.”

There was a very long silence before I said, “Well guys, I guess I did. This is going to take sometime,” as I thought I wonder if any one on the crew of that B-52 was ever asked by a teen, “Have you ever seen a UFO?”